Genuinely Relevant Math

“When am I ever going to use this?”

For years, students in high school math classes have asked this question. For years, they’ve been given unsatisfying answers - or just ignored. We decided to change that.

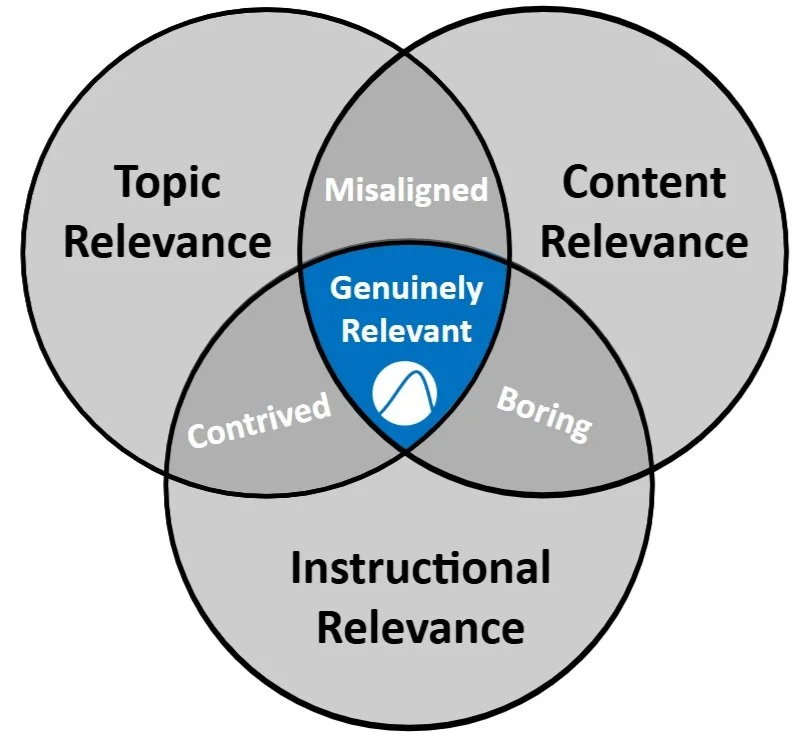

Started by teachers, Skew The Script provides free Genuinely Relevant Math lessons. Specifically, our lessons meet the three criteria for genuine relevance:

Topic Relevance: The context is compelling

The lessons explore contexts that are authentically meaningful, compelling, and important to students’ lives.

-

To engage all students, we can’t make the promise that math will, at some point in the vague future, be relevant. Especially for students who work jobs outside of school, support their families, and manage complex problems on a regular basis, this vague promise can feel like an empty one. The math needs to be helpful, useful, and relevant now. Relevant contexts make these connections current and clear.

Content Relevance: The math is essential

The math isn’t a side-show or veneer. Rather, the math is central, and it provides genuine insight into the context.

-

Students should walk away feeling that the math skills they learned were essential for understanding key aspects of the lesson context. Otherwise, while the context may have been relevant, the math used in the lesson will continue to feel like an irrelevant add-on.

Instructional Relevance: The material is instructionally useful

The lessons fit into teachers’ calendars, are aligned to math standards, and prepare students for the assessments they need to take.

-

Math teachers have a short amount of time to cover all the standards for their courses. In addition, for many courses, they have to prepare students for standardized tests. To be useful under these conditions, lessons must be created in well-chunked formats. They must be aligned to course standards. Finally, they must genuinely prepare students for the exams they need to take.

Problems that lack topic relevance -> Boring

Problems that lack content relevance -> Contrived

Problems that lack instructional relevance -> Misaligned

How do we meet all 3 relevance criteria? Using the Students First, Standards Last Method

In the typical curriculum creation process, lesson designers start with the math standards they need to cover. Then, they fit their lesson contexts and tasks to those standards. The result: lessons that are well-aligned to standards (Instructional Relevance) but with either boring contexts that lack Topic Relevance or contrived connections that lack Content Relevance.

Skew The Script takes an inverted approach. We consider the math standards last. That’s not to say that the math standards aren’t important - far from it! We believe that designing lessons aligned to math standards - and to the way those standards are tested - is essential. Otherwise, the lessons would lack Instructional Relevance and would be useless for most classrooms.

While not last in importance, math standards are saved for the last step of our creation process. We start at a very different place: asking students what they care about (Topic Relevance). Then, we see what math naturally surfaces when we start exploring those student-chosen contexts (Content Relevance). This ordering ensures that our lessons investigate compelling contexts, using math that genuinely fits those contexts. Finally, when choosing which ideas to build into full lessons, we only select those that utilized common math concepts from high school courses (Instructional Relevance). In this way, we ensure that all 3 relevance criteria are satisfied.